The second Klan: 1915–1944

Refounding in 1915

In 1915, three separate events acted as catalysts to the revival of the Klan:

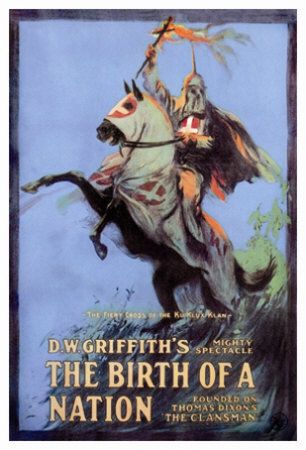

- The film The Birth of a Nation was released, mythologising and glorifying the first Klan and their endeavour.

- In 1915 Jewish businessman Leo Frank was lynched near Atlanta after the Georgia governor commuted his death sentence to life in prison. Frank had been convicted in 1913 and sentenced to death for the murder of a young white factory worker named Mary Phagan, in a trial marked by media frenzy. Although the conviction was appealed, it was upheld at each appellate level.

- The second Ku Klux Klan was founded in 1915 by William J. Simmons at Stone Mountain, outside Atlanta. Its growth was based on a new anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, prohibitionist and antisemitic agenda, which developed in response to contemporary social tensions. Most of the founders were from a small Atlanta-area organization called the Knights of Mary Phagan, who had organized around Leo Frank's trial. The new organization and chapters adopted regalia featured inThe Birth of a Nation.

The Birth of a Nation

Director D. W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation glorified the original Klan. His film was based on the book and play The Clansman and the book The Leopard's Spots, both by Thomas Dixon, Jr. Dixon said his purpose was "to revolutionize northern sentiment by a presentation of history that would transform every man in my audience into a good Democrat!" The film created a nationwide Klan craze. At the official premiere in Atlanta, members of the Klan rode up and down the street in front of the theater.[78]

Much of the modern Klan's iconography, including the standardized white costume and the lighted cross, are derived from the film. Its imagery was based on Dixon's romanticized concept of old England and Scotland, as portrayed in the novels and poetry of Sir Walter Scott. The film's influence was enhanced by a purported endorsement by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, a Southerner. A Hollywood press agent claimed that after seeing the film Wilson said, "It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true." Historians doubt he said it.[79] Wilson's remarks generated controversy, and he tried to remain aloof. On April 30, his staff issued a denial. Wilson's aide, Joseph Tumulty, said, "the President was entirely unaware of the nature of the play before it was presented and at no time has expressed his approbation of it."[80]

The new Klan was inaugurated in 1915 by William J. Simmons on top of Stone Mountain. It was a small local organization until 1921. Simmons said he had been inspired by the original Klan's Prescripts, written in 1867 by Confederate veteran George Gordon, but they were never adopted by the first Klan.[81]

Social factors

The Second Klan saw threats from every direction. A religious tone was present in its activities; "two-thirds of the national Klan lecturers were Protestant ministers," says historian Brian R. Farmer.[82]Much of the Klan's energy went to guarding "the home;" the historian Kathleen Bleeits said its members wanted to protect "the interests of white womanhood."[83]

The second Klan emerged during the nadir of American race relations, but much of its growth was in response to new issues of urbanization, immigration and industrialization. The massive immigration of Catholics and Jews from eastern and southern Europe led to fears among Protestants about the new peoples, and especially about job and social competition. The Great Migration of African Americans to the North stoked job and housing competition and racism by whites in Midwestern and Western industrial cities. The second Klan achieved its greatest political power in Indiana; it was active throughout the South, Midwest, especially Michigan; and in the West, in Colorado and Oregon. The migration of both African Americans and whites from rural areas to Southern and Midwestern cities increased social tensions.

The Klan became most prominent in urbanizing cities with high growth rates between 1910 and 1930, such as Detroit, Memphis, and Dayton in the Upper South and Midwest; and Atlanta, Dallas, andHouston in the South. In Michigan, close to 50% of the Klan members lived in Detroit, where they numbered 40,000; they were concerned about with finite housing possibilities, rapid social change, and competition for jobs with European immigrants and Southerners both black and white.[84] Stanley Horn, a Southern historian sympathetic to the first Klan, was careful in an oral interview to distinguish it from the later "spurious Ku Klux organization which was in ill-repute—and, of course, had no connection whatsoever with the Klan of Reconstruction days".[85]

In an era without Social Security or widely available life insurance, men joined fraternal organizations such as the Elks or the Woodmen of the World to provide for their families in case they died or were unable to work. The founder of the new Klan, William J. Simmons, was a member of twelve different fraternal organizations. He recruited for the Klan with his chest covered with fraternal badges, and consciously modeled the Klan after fraternal organizations.[86]

Klan organizers, called "Kleagles", signed up hundreds of new members, who paid initiation fees and received KKK costumes in return. The organizer kept half the money and sent the rest to state or national officials. When the organizer was done with an area, he organized a huge rally, often with burning crosses, and perhaps presented a Bible to a local Protestant preacher. He left town with the money collected. The local units operated like many fraternal organizations and occasionally brought in speakers.

The Klan's growth was also affected by the mobilization for World War I and postwar tensions, especially in the cities, where strangers came up against each other more often and competed for housing and jobs. Southern whites resented the arming of black soldiers. Black veterans did not want to return to second-class status in the South. Some black veterans in the South were lynched while still in uniform, after returning from overseas service.[87]

Activities

Simmons initially met with little success in either recruiting members or in raising money, and the Klan remained a small operation in the Atlanta area until 1920, when he handed its day-to-day activities over to two professional publicists,Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke.[88] The revived Klan appealed to new members based on current social tensions, and stressed responses to fears raised by immigration and mass migrations within industrializing cities: it becameanti-Jewish, anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant and later anti-Communist. It presented itself as a fraternal, nativist and strenuously patriotic organization; and its leaders emphasized support for vigorous enforcement of prohibition laws. It expanded membership dramatically; by the 1920s, most of its members lived in the Midwest and West. It had a national base by 1925.

Religion was a major selling point. Baker argues that Klansmen seriously embraced Protestantism as an essential component of their white supremacist, anti-Catholic, and paternalistic formulation of American democracy and national culture. Their cross was a religious symbol, and their ritual honored Bibles and local ministers. However no nationally prominent religious leader said he was a Klan member.[89]

Prohibition

Historians agree that the Klan's resurgence in the 1920s was aided by the national debate over prohibition.[90] The historian Prendergast says that the KKK’s "support for Prohibition represented the single most important bond between Klansmen throughout the nation".[91] The Klan opposed bootleggers, sometimes with violence. In 1922, two hundred Klan members set fire to saloons in Union County, Arkansas. The national Klan office was established in Dallas, Texas, butLittle Rock, Arkansas was the home of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan. The first head of this auxiliary was a former president of the Arkansas WCTU.[92][verification needed] Membership in the Klan and in other prohibition groups overlapped, and they often coordinated activities.[93]

Urbanization

A significant characteristic of the second Klan was that it was an organization based in urban areas, reflecting the major shifts of population to cities in both the North and the South. In Michigan, for instance, 40,000 members lived in Detroit, where they made up more than half of the state's membership. Most Klansmen were lower- to middle-class whites who were trying to protect their jobs and housing from the waves of newcomers to the industrial cities: immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, who tended to be Catholic and Jewish in numbers higher than earlier groups of immigrants; and black and white migrants from the South. As new populations poured into cities, rapidly changing neighborhoods created social tensions. Because of the rapid pace of population growth in industrializing cities such as Detroit and Chicago, the Klan grew rapidly in the U.S. Midwest. The Klan also grew in booming Southern cities such as Dallas and Houston.[94]

In the medium-size industrial city of Worcester, Massachusetts in the 1920s, the Klan ascended to power quickly but declined as a result of opposition from the Catholic Church. There was no violence and the local newspaper ridiculed Klansmen as "night-shirt knights". Half of the members were Swedish American, including some first-generation immigrants. The ethnic and religious conflicts among more recent immigrants contributed to the rise of the Klan in the city. Swedish Protestants were struggling against Irish Catholics, who had been entrenched longer, for political and ideological control of the city.[95]

For some states, historians have obtained membership rosters of some local units and matched the names against city directory and local records to create statistical profiles of the membership. Big city newspapers were often hostile and ridiculed Klansmen as ignorant farmers. Detailed analysis from Indiana showed the rural stereotype was false for that state:

Indiana's Klansmen represented a wide cross section of society: they were not disproportionately urban or rural, nor were they significantly more or less likely than other members of society to be from the working class, middle class, or professional ranks. Klansmen were Protestants, of course, but they cannot be described exclusively or even predominantly as fundamentalists. In reality, their religious affiliations mirrored the whole of white Protestant society, including those who did not belong to any church.[96]

The Klan attracted people but most of them did not remain in the organization for long. Membership in the Klan turned over rapidly as people found out that it was not the group they wanted. Millions joined, and at its peak in the 1920s, the organization included about 15% of the nation's eligible population. The lessening of social tensions contributed to the Klan's decline.

The burning cross

The second Klan embraced a burning Latin cross primarily as a symbol of intimidation.[97] No crosses had been used as a symbol by the first Klan. Additionally, the cross was henceforth a representation of the Klan's Christian message. Thus, its lighting during meetings was often accompanied by prayer, the singing of hymns, and other overtly religious symbolism.[14]

The practice of cross burning had been loosely based on ancient Scottish clans' burning a St. Andrew's cross (an X-shaped cross) as a beacon to muster forces for war. In The Clansman (see above), Dixon had falsely claimed that the first Klan had used fiery crosses when rallying to fight against Reconstruction. Griffith brought this image to the screen in The Birth of a Nation; he portrayed the burning cross as an upright Latin cross rather than the St. Andrew's cross. Simmons adopted the symbol wholesale from the movie, prominently displaying it at the 1915 Stone Mountain meeting. The symbol has been associated with the Klan ever since.[98]

Education

In 1921, in an attempt to gain a foothold in education, the Klan bought Lanier University, a struggling Baptist university in Atlanta. Nathan Bedford Forrest, grandson of the Confederate general by the same name, was appointed its business manager. The school was to teach "pure, 100 percent Americanism". Enrollment was dismal, and the school closed after the first year of Klan ownership.[99]

Women

By the 1920s, the KKK developed a women's auxiliary, with chapters in many areas. Its activities included participation in parades, cross lighting, lectures, rallies, and boycotts of local businesses owned by Catholics and Jews. The Women's Klan were active in promoting prohibition, stressing liquor's negative impact on wives and children. Their efforts in public schools included distributing Bibles and working for the dismissal of Roman Catholic teachers. Texas would not hire Catholic teachers in public schools. As scandals rocked the Klan leadership late in the 1920s, the organization's popularity among both men and women dropped off sharply.[100]

Political role

The members of the first Klan in the South were exclusively Democrats. The second Klan expanded with new chapters in the Midwest and West, where for a time, its members were courted by bothRepublicans and Democrats. The KKK state organizations endorsed candidates from either party that supported its goals; Prohibition in particular helped the Klan and some Republicans to make common cause in the Midwest.

The Klan had numerous members in every part of the United States, but was particularly strong in the South and Midwest. At its peak, claimed Klan membership exceeded four million and comprised 20% of the adult white male population in many broad geographic regions, and 40% in some areas.[101] The Klan also moved north into Canada, especially Saskatchewan, where it opposed Catholics.[102]

With expanded membership came election of Klan members to political office. In Indiana, members were chiefly American-born, white Protestants of many income and social levels. In the 1920s, Indiana had the most powerful Ku Klux Klan in the nation. It had a high number of members statewide (over 30% of its white male citizens[103]), and in 1924 elected the Klan member Edward Jacksonas governor.[104]

Given success in state and local elections, the Klan issue contributed to the bitterly divisive 1924 Democratic National Convention in New York City. The leading candidates were William Gibbs McAdoo, a Protestant with a base in areas where the Klan was strong, and New York Governor Al Smith, a Catholic with a base in the large cities. After weeks of stalemate, both candidates withdrew in favor of a compromise. Anti-Klan delegates proposed a resolution indirectly attacking the Klan; it was narrowly defeated.[105][106]

In some states, such as Alabama and California, KKK chapters had worked for political reform. In 1924, Klan members were elected to the city council inAnaheim, California. The city had been controlled by an entrenched commercial-civic elite that was mostly German American. Given their tradition of moderate social drinking, the German Americans did not strongly support prohibition laws—the mayor had been a saloon keeper. Led by the minister of the First Christian Church, the Klan represented a rising group of politically oriented non-ethnic Germans who denounced the elite as corrupt, undemocratic and self-serving. The historian Christopher Cocoltchos says the Klansmen tried to create a model, orderly community. The Klan had about 1200 members in Orange County, California. The economic and occupational profile of the pro and anti-Klan groups shows the two were similar and about equally prosperous. Klan members were Protestants, as were most of their opponents, but the latter also included many Catholic Germans. Individuals who joined the Klan had earlier demonstrated a much higher rate of voting and civic activism than did their opponents. Cocoltchos suggests that many of the individuals in Orange County joined the Klan out of that sense of civic activism. The Klan representatives easily won the local election in Anaheim in April 1924. They fired known city employees who were Catholic and replaced them with Klan appointees. The new city council tried to enforce prohibition. After its victory, the Klan chapter held large rallies and initiation ceremonies over the summer.[107]

The opposition organized, bribed a Klansman for the secret membership list, and exposed the Klansmen running in the state primaries; they defeated most of the candidates. Klan opponents in 1925 took back local government, and succeeded in a special election in recalling the Klansmen who had been elected in April 1924. The Klan in Anaheim quickly collapsed, its newspaper closed after losing a libel suit, and the minister who led the local Klavern moved to Kansas.[107]

In the South, Klan members were still Democratic, as it was a one-party region for whites. Klan chapters were closely allied with Democratic police, sheriffs, and other functionaries of local government. Since disfranchisement of most African Americans and many poor whites around the start of the 20th century, the only political activity for whites took place within the Democratic Party.

In Alabama, Klan members advocated better public schools, effective prohibition enforcement, expanded road construction, and other political measures to benefit lower-class white people. By 1925, the Klan was a political force in the state, as leaders such as J. Thomas Heflin, David Bibb Graves, and Hugo Black tried to build political power against the Black Belt planters, who had long dominated the state.[108] In 1926, with Klan support, Bibb Graves won the Alabama governor's office. He was a former Klan chapter head. He pushed for increased education funding, better public health, new highway construction, and pro-labor legislation. Because the Alabama state legislature refused to redistrict until 1972, and then under court order, the Klan was unable to break the planters' and rural areas' hold on legislative power. Scholars and biographers have recently examined Hugo Black's Klan role. Ball finds regarding the KKK that Black "sympathized with the group's economic, nativist, and anti-Catholic beliefs."[109] Newman says Black "disliked the Catholic Church as an institution" and gave over 100 anti-Catholic speeches in his 1926 election campaign to KKK meetings across Alabama.[110]Black was elected US senator in 1926 as a Democrat. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1937 appointed Black to the Supreme Court without knowing how active in the Klan he had been in the 1920s. He was confirmed by his fellow Senators before the full KKK connection was known; Justice Black said he left the Klan when he became a senator.[111]

Resistance and decline

Many groups and leaders, including prominent Protestant ministers such as Reinhold Niebuhr in Detroit, spoke out against the Klan, gaining national attention. The Jewish Anti-Defamation League was formed in the early 20th century after the lynching of Leo Frank, and in response to attacks against Jewish Americans and the Klan's campaign to outlaw private schools. Opposing groups worked to penetrate the Klan's secrecy. After one civic group began to publish Klan membership lists, there was a rapid decline in members. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People created public education campaigns in order to inform people about Klan activities and lobbied in Congress against Klan abuses. After its peak in 1925, Klan membership in most areas began to decline rapidly.[94]

Specific events contributed to the decline as well. In Indiana, the scandal surrounding the 1925 murder trial of Grand Dragon D.C. Stephenson destroyed the image of the KKK as upholders of law and order. By 1926 the Klan was "crippled and discredited."[104] D. C. Stephenson was the Grand Dragon of Indiana and 22 northern states. In 1923 he had led the states under his control to separate from the national KKK organization. In his 1925 trial, he was convicted for second degree murder for his part in the rape and subsequent death[112] of Madge Oberholtzer. After Stephenson's conviction, the Klan declined dramatically in Indiana. The historian Leonard Moore says that a failure in leadership caused the Klan's collapse:

Stephenson and the other salesmen and office seekers who maneuvered for control of Indiana's Invisible Empire lacked both the ability and the desire to use the political system to carry out the Klan's stated goals. They were uninterested in, or perhaps even unaware of, grass roots concerns within the movement. For them, the Klan had been nothing more than a means for gaining wealth and power. These marginal men had risen to the top of the hooded order because, until it became a political force, the Klan had never required strong, dedicated leadership. More established and experienced politicians who endorsed the Klan, or who pursued some of the interests of their Klan constituents, also accomplished little. Factionalism created one barrier, but many politicians had supported the Klan simply out of expedience. When charges of crime and corruption began to taint the movement, those concerned about their political futures had even less reason to work on the Klan's behalf.[113]

By 1920 Klan membership in Alabama dropped to less than 6,000. Small independent units continued to be active in the industrial city of Birmingham. In the late 1940s and 1950s, members launched a reign of terror by bombing the homes of upwardly mobile African Americans. Activism by such independent KKK groups increased as a reaction against the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

In Alabama, KKK vigilantes launched a wave of physical terror in 1927. They targeted both blacks and whites for violation of racial norms and for perceived moral lapses.[114] This led to a strong backlash, beginning in the media. Grover C. Hall, Sr., editor of the Montgomery Advertiser from 1926, wrote a series of editorials and articles that attacked the Klan. (Today the paper says it "waged war on the resurgent [KKK]".)[115] Hall won a Pulitzer Prize for the crusade, the 1928 Editorial Writing Pulitzer, citing "his editorials against gangsterism, floggings and racial and religious intolerance."[116][117] Other newspapers kept up a steady, loud attack on the Klan, referring to the organization as violent and "un-American". Sheriffs cracked down on activities. In the 1928 presidential election, the state voters overcame initial opposition to the Catholic candidate Al Smith, and voted the Democratic Party line as usual.

Although in decline, a measure of the Klan's influence was its march along Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC in 1928.

Labor and anti-unionism

In southern cities such as Birmingham, Alabama, Klan members kept control of access to the better-paying industrial jobs and opposed unions. During the 1930s and 1940s, Klan leaders urged members to disrupt the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), which advocated industrial unions and accepted African-American members, unlike earlier unions. With access to dynamite and using the skills from their jobs in mining and steel, in the late 1940s some Klan members in Birmingham used bombings in order to intimidate upwardly mobile blacks who moved into middle-class neighborhoods. "By mid-1949, there were so many charred house carcasses that the area [College Hills] was informally named Dynamite Hill."[118] Independent Klan groups remained active in Birmingham and violently opposed the Civil Rights Movement.[118]

In 1939, after years of the Great Depression, the Imperial Wizard Hiram Wesley Evans sold the national organization to James Colescott, an Indiana veterinarian, and Samuel Green, an Atlanta obstetrician. They could not revive the declining membership. In 1944, the IRS filed a lien for $685,000 in back taxes against the Klan, and Colescott dissolved the organization that year. Local Klan groups closed over the following years.[119]

Due in part to lynchings and Klan terror directed against them, from the early 1900s to 1940, 1.5 million blacks left the South in the Great Migration to northern and midwestern industrial cities. Many were recruited by expanding industries in the North, such as the Pennsylvania Railroad and industries in Chicago and Omaha. Although Southern violence had declined, better economic, educational, and voting opportunities in other areas attracted another 5 million blacks to migrate out of the South from 1940-1970, with many going to West Coast cities, a center of defense industry jobs.

After World War II, the folklorist and author Stetson Kennedy infiltrated the Klan; he provided internal data to media and law enforcement agencies. He also provided secret code words to the writers of the Superman radio program, resulting in episodes in which Superman took on the KKK. Kennedy stripped away the Klan's mystique and trivialized its rituals and code words, which may have contributed to the decline in Klan recruiting and membership.[120] In the 1950s, Kennedy wrote a bestselling book about his experiences, which further damaged the Klan.[121]

The following table shows the change in the Klan's estimated membership over time.[122] (The years given in the table represent approximate time periods.)

| Year | Membership |

|---|---|

| 1920 | 4,000,000[123] |

| 1924 | 6,000,000 |

| 1930 | 30,000 |

| 1980 | 5,000 |

| 2008 | 6,000 |

Later Klans, 1950 through 1960s

The name "Ku Klux Klan" began to be used by several independent groups. Beginning in the 1950s, for instance, individual Klan groups in Birmingham, Alabama, began to resist social change and blacks' improving their lives by bombing houses in transitional neighborhoods. There were so many bombings in Birmingham of blacks' homes by Klan groups in the 1950s that the city's nickname was "Bombingham".[24]

During the tenure of Bull Connor as police commissioner in the city, Klan groups were closely allied with the police and operated with impunity. When the Freedom Riders arrived in Birmingham, Connor gave Klan members fifteen minutes to attack the riders before sending in the police to quell the attack.[24] When local and state authorities failed to protect the Freedom Riders and activists, the federal government established effective intervention.

In states such as Alabama and Mississippi, Klan members forged alliances with governors' administrations.[24] In Birmingham and elsewhere, the KKK groups bombed the houses of civil rights activists. In some cases they used physical violence, intimidation and assassination directly against individuals. Many murders went unreported and were not prosecuted by local and state authorities.[citation needed] Continuing disfranchisement of blacks across the South meant that most could not serve on juries, which were all white.

According to a report from the Southern Regional Council in Atlanta, the homes of 40 black Southern families were bombed during 1951 and 1952. Some of the bombing victims were social activists whose work exposed them to danger, but most were either people who refused to bow to racist convention or were innocent bystanders, unsuspecting victims of random violence.[124]

Among the more notorious murders by Klan members:

- The 1951 Christmas Eve bombing of the home of National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) activists Harry and Harriette Moore in Mims, Florida, resulting in their deaths.[125]

- The 1957 murder of Willie Edwards, Jr. Klansmen forced Edwards to jump to his death from a bridge into the Alabama River.[126]

- The 1963 assassination of NAACP organizer Medgar Evers in Mississippi. In 1994, former Ku Klux Klansman Byron De La Beckwith was convicted.

- The 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed four African-American girls. The perpetrators were Klan members Robert Chambliss, convicted in 1977, Thomas Edwin Blanton, Jr. and Bobby Frank Cherry, convicted in 2001 and 2002. The fourth suspect, Herman Cash, died before he was indicted.

- The 1964 murders of three civil rights workers, Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, in Mississippi. In June 2005, Klan member Edgar Ray Killen was convicted of manslaughter.[127]

- The 1964 murder of two black teenagers, Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore in Mississippi. In August 2007, based on the confession of Klansman Charles Marcus Edwards, James Ford Seale, a reputed Ku Klux Klansman, was convicted. Seale was sentenced to serve three life sentences. Seale was a former Mississippi policeman and sheriff's deputy.[128]

- The 1965 Alabama murder of Viola Liuzzo. She was a Southern-raised Detroit mother of five who was visiting the state in order to attend a civil rights march. At the time of her murder Liuzzo was transporting Civil Rights Marchers.

- The 1966 firebombing death of NAACP leader Vernon Dahmer Sr., 58, in Mississippi. In 1998 former Ku Klux Klan wizard Sam Bowers was convicted of his murder and sentenced to life. Two other Klan members were indicted with Bowers, but one died before trial, and the other's indictment was dismissed.

Resistance

There was also resistance to the Klan. In 1953, newspaper publishers W. Horace Carter (Tabor City, NC), who had campaigned for three years, and Willard Cole (Whiteville, NC) shared the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service citing "their successful campaign against the Ku Klux Klan, waged on their own doorstep at the risk of economic loss and personal danger, culminating in the conviction of over one hundred Klansmen and an end to terrorism in their communities."[129] In a 1958 incident in North Carolina, the Klan burned crosses at the homes of two Lumbee Native Americans who had associated with white people, and they threatened to return with more men. When the KKK held a nighttime rally nearby, they were quickly surrounded by hundreds of armed Lumbees. Gunfire was exchanged, and the Klan was routed at what became known as the Battle of Hayes Pond.[130]

While the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had paid informants in the Klan, for instance in Birmingham in the early 1960s, its relations with local law enforcement agencies and the Klan were often ambiguous. The head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, appeared more concerned about Communist links to civil rights activists than about controlling Klan excesses against citizens. In 1964, the FBI's COINTELPRO program began attempts to infiltrate and disrupt civil rights groups.[24]

As 20th-century Supreme Court rulings extended federal enforcement of citizens' civil rights, the government revived the Force Acts and the Klan Act from Reconstruction days. Federal prosecutors used these laws as the basis for investigations and indictments in the 1964 murders of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner;[131] and the 1965 murder of Viola Liuzzo. They were also the basis for prosecution in 1991 in Bray v. Alexandria Women's Health Clinic.

TO BE CONTINUED

No comments:

Post a Comment