Ku Klux Klan

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"KKK" redirects here. For other uses, see KKK (disambiguation).

Ku Klux Klan's logo

| |

| In existence | |

|---|---|

| 1st Klan | 1865–1870s |

| 2nd Klan | 1915–1944 |

| 3rd Klan[notes 1] | since 1946 |

| Members | |

| 1st Klan | 550,000[citation needed] |

| 2nd Klan | 3,000,000–6,000,000[2] (peaked in 1920–1925 period) |

| 3rd Klan | 5,000-8,000[3] |

| Properties | |

| Origin | United States of America |

| Political ideology | White supremacy White nationalism Nativism[4] Anti-communism Christian terrorism[5][6] Anti-Catholicism Antisemitism Homophobism Neo-fascism (Third KKK) |

| Political position | Far-right |

| Religion | Protestantism |

The first Ku Klux Klan flourished in the Southern United States in the late 1860s, then died out by the early 1870s. Members adopted white costumes: robes, masks, and conical hats, designed to be outlandish and terrifying, and to hide their identities.[13] The second KKK flourished nationwide in the early and mid-1920s, and adopted the same costumes and code words as the first Klan, while introducing cross burnings.[14] The third KKK emerged after World War II and was associated with opposing the Civil Rights Movement and progress among minorities. The second and third incarnations of the Ku Klux Klan made frequent reference to the USA's "Anglo-Saxon" blood, harking back to 19th-century nativism and claiming descent from the original 18th-century British colonial revolutionaries.[15]

Contents

[hide]Overview: Three Klans

First KKK

The first Klan was founded in 1865 in Pulaski, Tennessee, by six veterans of the Confederate Army.[16] The name is probably derived from the Greek word kuklos (κύκλος) which means circle, suggesting a circle or band of brothers.[17]Although there was little organizational structure above the local level, similar groups rose across the South and adopted the same name and methods.[18] Klan groups spread throughout the South as an insurgent movement during the Reconstruction era in the United States. As a secret vigilante group, the Klan targeted freedmen and their allies; it sought to restore white supremacy by threats and violence, including murder, against black and white Republicans. In 1870 and 1871, the federal government passed the Force Acts, which were used to prosecute Klan crimes.[19] Prosecution of Klan crimes and enforcement of the Force Acts suppressed Klan activity. In 1874 and later, however, newly organized and openly active paramilitary organizations, such as the White League and the Red Shirts, started a fresh round of violence aimed at suppressing blacks' voting and running Republicans out of office. These contributed to segregationist white Democrats regaining political power in all the Southern states by 1877.

Second KKK

In 1915, the second Klan was founded in Atlanta, Georgia. Starting in 1921, it adopted a modern business system of recruiting (which paid most of the initiation fee and costume charges as commissions to the organizers) and grew rapidly nationwide at a time of prosperity. Reflecting the social tensions of urban industrialization and vastly increased immigration, its membership grew most rapidly in cities, and spread out of the South to the Midwest and West. The second KKK preached "One Hundred Percent Americanism" and demanded the purification of politics, calling for strict morality and better enforcement of prohibition. Its official rhetoric focused on the threat of the Catholic Church, using anti-Catholicism and nativism.[4] Its appeal was directed exclusively at white Protestants.[20] Some local groups took part in attacks on private houses and carried out other violent activities. The violent episodes were generally in the South.[21]The second Klan was a formal fraternal organization, with a national and state structure. At its peak in the mid-1920s, the organization claimed to include about 15% of the nation's eligible population, approximately 4–5 million men. Internal divisions, criminal behavior by leaders, and external opposition brought about a collapse in membership, which had dropped to about 30,000 by 1930. It finally faded away in the 1940s.[22] Klan organizers also operated in Canada, especially in Saskatchewan in 1926-28, where members of the Klan attacked immigrants from Eastern Europe.[23]

Third KKK

The "Ku Klux Klan" name was used by a numerous independent local groups opposing the Civil Rights Movement and desegregation, especially in the 1950s and 1960s. During this period, they often forged alliances with Southern police departments, as in Birmingham, Alabama; or with governor's offices, as with George Wallace of Alabama.[24] Several members of KKK groups were convicted of murder in the deaths of civil rights workers and children in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham. Today, researchers estimate that there may be 150 Klan chapters with upwards of 5,000 members nationwide.[25]Today, many sources classify the Klan as a "subversive or terrorist organization".[25][26][27][28] In April 1997, FBI agents arrested four members of the True Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in Dallas for conspiracy to commit robbery and to blow up a natural gas processing plant.[29] In 1999, the city council of Charleston, South Carolina passed a resolution declaring the Klan to be a terrorist organization.[30] In 2004, a professor at the University of Louisville began a campaign to have the Klan declared a terrorist organization in order to ban it from campus.[31]

First Klan 1865–1874

Creation and naming

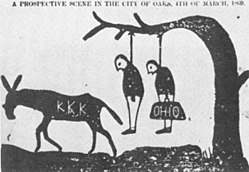

A cartoon threatening that the KKK would lynch carpetbaggers. From the Independent Monitor, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, 1868.

Historians generally see the KKK as part of the post Civil War insurgent violence related not only to the high number of veterans in the population, but also to their effort to control the dramatically changed social situation by using extrajudicial means to restore white supremacy. In 1866, Mississippi Governor William L. Sharkey reported that disorder, lack of control and lawlessness were widespread; in some states armed bands of Confederate soldiers roamed at will. The Klan used public violence against blacks as intimidation. They burned houses, and attacked and killed blacks, leaving their bodies on the roads.[36]

At an 1867 meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, Klan members gathered to try to create a hierarchical organization with local chapters eventually reporting up to a national headquarters. Since most of the Klan's members were veterans, they were used to the hierarchical structure of the organization, but the Klan never operated under this centralized structure. Local chapters and bands were highly independent.

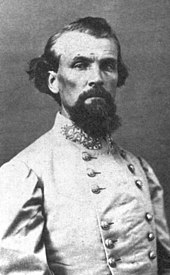

Former Confederate Brigadier General George Gordon developed the Prescript, or Klan dogma. The Prescript suggested elements of white supremacist belief. For instance, an applicant should be asked if he was in favor of "a white man's government", "the reenfranchisement and emancipation of the white men of the South, and the restitution of the Southern people to all their rights."[37] The latter is a reference to the Ironclad Oath, which stripped the vote from white persons who refused to swear that they had not borne arms against the Union. Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest became Grand Wizard, claiming to be the Klan's national leader.[16][38]

In an 1868 newspaper interview, Forrest stated that the Klan's primary opposition was to the Loyal Leagues, Republican state governments, people like Tennessee governor Brownlow and other carpetbaggers and scalawags.[39][40] He argued that many southerners believed that blacks were voting for the Republican Party because they were being hoodwinked by the Loyal Leagues.[41] One Alabama newspaper editor declared "The League is nothing more than a nigger Ku Klux Klan."[42]

Despite Gordon's and Forrest's work, local Klan units never accepted the Prescript and continued to operate autonomously. There were never hierarchical levels or state headquarters. Klan members used violence to settle old feuds and local grudges, as they worked to restore white dominance in the disrupted postwar society. The historian Elaine Frantz Parsons describes the membership:

Lifting the Klan mask revealed a chaotic multitude of antiblack vigilante groups, disgruntled poor white farmers, wartime guerrilla bands, displaced Democratic politicians, illegal whiskey distillers, coercive moral reformers, sadists, rapists, white workmen fearful of black competition, employers trying to enforce labor discipline, common thieves, neighbors with decades-old grudges, and even a few freedmen and white Republicans who allied with Democratic whites or had criminal agendas of their own. Indeed, all they had in common, besides being overwhelmingly white, southern, and Democratic, was that they called themselves, or were called, Klansmen.[43]Historian Eric Foner observed:

In effect, the Klan was a military force serving the interests of the Democratic party, the planter class, and all those who desired restoration of white supremacy. Its purposes were political, but political in the broadest sense, for it sought to affect power relations, both public and private, throughout Southern society. It aimed to reverse the interlocking changes sweeping over the South during Reconstruction: to destroy the Republican party's infrastructure, undermine the Reconstruction state, reestablish control of the black labor force, and restore racial subordination in every aspect of Southern life.[44]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Activities

Three Ku Klux Klan members arrested in Tishomingo County, Mississippi, September 1871, for the attempted murder of an entire family[citation needed]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Klan attacked black members of the Loyal Leagues and intimidated southern Republicans and Freedmen's Bureau workers. When they killed black political leaders, they also took heads of families, along with the leaders of churches and community groups, because these people had many roles in society. Agents of the Freedmen's Bureau reported weekly assaults and murders of blacks. "Armed guerrilla warfare killed thousands of Negroes; political riots were staged; their causes or occasions were always obscure, their results always certain: ten to one hundred times as many Negroes were killed as whites." Masked men shot into houses and burned them, sometimes with the occupants still inside. They drove successful black farmers off their land. "Generally, it can be reported that in North and South Carolina, in 18 months ending in June 1867, there were 197 murders and 548 cases of aggravated assault."[48]

In the April 1868 Georgia gubernatorial election, Columbia County cast 1,222 votes for Republican Rufus Bullock. By the November presidential election, however, Klan intimidation led to suppression of the Republican vote and only one person voted for Ulysses S. Grant.[50]

Klansmen killed more than 150 African Americans in a county in Florida, and hundreds more in other counties. Freedmen's Bureau records provided a detailed recounting of Klansmen's beatings and murders of freedmen and their white allies.[51]

Milder encounters also occurred. In Mississippi, according to the Congressional inquiry:[52]

One of these teachers (Miss Allen of Illinois), whose school was at Cotton Gin Port in Monroe County, was visited ... between one and two o'clock in the morning on March 1871, by about fifty men mounted and disguised. Each man wore a long white robe and his face was covered by a loose mask with scarlet stripes. She was ordered to get up and dress which she did at once and then admitted to her room the captain and lieutenant who in addition to the usual disguise had long horns on their heads and a sort of device in front. The lieutenant had a pistol in his hand and he and the captain sat down while eight or ten men stood inside the door and the porch was full. They treated her "gentlemanly and quietly" but complained of the heavy school-tax, said she must stop teaching and go away and warned her that they never gave a second notice. She heeded the warning and left the county.By 1868, two years after the Klan's creation, its activity was beginning to decrease.[53] Members were hiding behind Klan masks and robes as a way to avoid prosecution for freelance violence. Many influential southern Democrats feared that Klan lawlessness provided an excuse for the federal government to retain its power over the South, and they began to turn against it.[54] There were outlandish claims made, such as Georgian B. H. Hill stating "that some of these outrages were actually perpetrated by the political friends of the parties slain."[53]

Resistance

Union Army veterans in mountainous Blount County, Alabama, organized "the anti-Ku Klux". They put an end to violence by threatening Klansmen with reprisals unless they stopped whipping Unionists and burning black churches and schools. Armed blacks formed their own defense in Bennettsville, South Carolina and patrolled the streets to protect their homes.[55]National sentiment gathered to crack down on the Klan, even though some Democrats at the national level questioned whether the Klan really existed or believed that it was just a creation of nervous Southern Republican governors.[56] Many southern states began to pass anti-Klan legislation.[citation needed]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Decline and replacement by other groups

Although Forrest boasted that the Klan was a nationwide organization of 550,000 men and that he could muster 40,000 Klansmen within five days' notice, as a secret or "invisible" group, it had no membership rosters, no chapters, and no local officers. It was difficult for observers to judge its actual membership.[63] It had created a sensation by the dramatic nature of its masked forays and because of its many murders.In 1870 a federal grand jury determined that the Klan was a "terrorist organization".[64] It issued hundreds of indictments for crimes of violence and terrorism. Klan members were prosecuted, and many fled from areas that were under federal government jurisdiction, particularly in South Carolina.[65] Many people not formally inducted into the Klan had used the Klan's costume for anonymity, to hide their identities when carrying out acts of violence. Forrest called for the Klan to disband in 1869, arguing that the Klan was "being perverted from its original honorable and patriotic purposes, becoming injurious instead of subservient to the public peace".[66] Stanley Horn, a Klan historian argues that "generally speaking, the Klan's end was more in the form of spotty, slow, and gradual disintegration than a formal and decisive disbandment".[67] Moreover, a Georgia based reporter wrote in 1870 that, "A true statement of the case is not that the Ku Klux are an organized band of licensed criminals, but that men who commit crimes call themselves Ku Klux".[68]

Others may have agreed with lynching as a way of keeping dominance over black men. In many states, officials were reluctant to use black militia against the Klan out of fear that racial tensions would be raised.[62] When Republican Governor of North Carolina William Woods Holden called out the militia against the Klan in 1870, it added to his unpopularity. Combined with violence and fraud at the polls, the Republicans lost their majority in the state legislature. Disaffection with Holden's actions led to white Democratic legislators' impeaching Holden and removing him from office, but their reasons were numerous.[69]

The Klan was virtually removed in South Carolina[70] and gradually withered away throughout the rest of the South where it had gradually been faltering in prominence. Attorney General Amos Tappan Ackerman led the prosecutions.[71]

In some areas, other local paramilitary organizations such as the White League, Red Shirts, saber clubs, and rifle clubs continued to intimidate and murder black voters.[72]

In 1874, organized white paramilitary groups were formed in the Deep South to replace the faltering Klan: the White League in Louisiana and the Red Shirts in Mississippi, North and South Carolina. They campaigned openly to turn Republicans out of office, intimidated and killed black voters, tried to disrupt organizing and suppressed black voting. They were out in force during the campaigns and elections of 1874 and 1876, contributing to the conservative Democrats regaining power in 1876, against a background of electoral violence.

Shortly after, in United States v. Cruikshank (1875), the Supreme Court ruled that the Force Act of 1870 did not give the Federal government power to regulate private actions, but only those by state governments. The result was that as the century went on, African Americans were at the mercy of hostile state governments that refused to intervene against private violence and paramilitary groups.

Whereas the number of indictments across the South was large, the number of cases leading to prosecution and sentencing was relatively small. The overloaded federal courts were not able to meet the demands of trying such a tremendous number of cases, a situation that led to selective pardoning. By late 1873 and 1874, most of the charges against Klansmen were dropped although new cases continued to be prosecuted for several more years. Most of those sentenced had either served their terms or had been pardoned by 1875.In 1882, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Harris that the Klan Act was partially unconstitutional. It ruled that Congress's power under the Fourteenth Amendment did not extend to the right to regulate against private conspiracies.[74]

The Supreme Court of the United States eviscerated the Ku Klux Act in 1876 by ruling that the federal government could no longer prosecute individuals although states would be forced to comply with federal civil rights provisions. Republicans passed a second civil rights act (the Civil Rights Act of 1875) to grant equal access to public facilities and other housing accommodations regardless of race. Ironically, the Klan during this period served to further Northern reconstruction efforts, as Ku Klux violence provided the political climate needed to pass civil rights protections for blacks. Although the Ku Klux Act of 1871 dismantled the first Klan, Southern whites formed other, similar groups that kept blacks away from the polls through intimidation and physical violence. Reconstruction ended with the election of President Rutherford B. Hayes, who suspended the federal military occupation of the South; yet blacks still found themselves without the basic civil liberties that Congressional Republicans had sought to secure.[73]

Klan costumes, also called "regalia", disappeared by the early 1870s (Wade 1987, p. 109). The fact that the Klan did not exist for decades was shown when Simmons's 1915 recreation of the Klan attracted only two aging "former Reconstruction Klansmen." All other members were new.[75] By 1872, the Klan was broken as an organization.[76] Nonetheless, the goals that the Klan had failed to achieve itself, such as suppressing suffrage for Southern blacks and driving a wedge between poor whites and blacks, were largely accomplished by the 1890s by militant Southern whites. Lynchings of African Americans, far from being ended by the Klan's disintegration, instead peaked in 1892 with 161 deaths.[77]

TO BE CONTINUED

No comments:

Post a Comment