I AM VERY GRATEFUL FOR WIKIPEDIA, AND I DO SUPPORT THEM EACH MONTH WITH A SMALL DONATION.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Apartheid" redirects here. For the legal definition of Apartheid, see crime of apartheid. For other uses, see Apartheid (disambiguation).

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid in South Africa |

|---|

| Part of a series on the |

| History of South Africa |

|---|

|

| General periods |

| Before 1652 |

| 1652 to 1815 |

| 1815 to 1910 |

| 1910 to 1948 |

| 1948 to 1994 |

| 1994 to present |

| Specific themes |

| Economic |

| Military |

| Slavery |

| Religious |

Apartheid (Afrikaans pronunciation: [ɐˈpɑːrtɦɛit]; an Afrikaans[1] word meaning 'the state of being apart', literally 'apart-hood'[2][3]) was a system of racial segregation in South Africa enforced through legislation by the National Party (NP) governments, the ruling party from 1948 to 1994, under which the rights of the majority black inhabitants were curtailed and Afrikaner minority rule was maintained. Apartheid was developed after World War II by the Afrikaner-dominated National Party and Broederbond organisations and was practised also in South West Africa, which was administered by South Africa under a League of Nations mandate (revoked in 1966 via United Nations Resolution 2145),[4] until it gained independence as Namibia in 1990.[5]

Racial segregation in South Africa began in colonial times under Dutch rule.[6] Apartheid as an official policy was introduced following the general election of 1948. Legislation classified inhabitants into four racial groups, "black", "white", "coloured", and "Indian", with Indian and coloured divided into several sub-classifications,[7] and residential areas were segregated, sometimes by forced removals. Non-white political representation was abolished in 1970, and starting in that year black people were deprived of their citizenship, legally becoming citizens of one of ten tribally based self-governing homelands called bantustans, four of which became nominally independent states. The government segregated education, medical care, beaches, and other public services, and provided black people with services inferior to those of white people.[8]

Apartheid sparked significant internal resistance and violence, and a long arms and trade embargo against South Africa.[9] Since the 1950s, a series of popular uprisings and protests was met with the banning of opposition and imprisoning of anti-apartheid leaders. As unrest spread and became more effective and militarised, state organisations responded with repression and violence. Along with the sanctions placed on South Africa by the West, this made it increasingly difficult for the government to maintain the regime.

Apartheid reforms in the 1980s failed to quell the mounting opposition, and in 1990 President Frederik Willem de Klerk began negotiations to end apartheid,[10]culminating in multi-racial democratic elections in 1994, won by the African National Congress under Nelson Mandela. The vestiges of apartheid still shape South African politics and society. Although the official abolishing of apartheid occurred in 1990 with repeal of the last of the remaining apartheid laws, the end of apartheid is widely regarded as arising from the 1994 democratic general elections.

- 1 Precursors of apartheid

- 2 Institution of apartheid

- 3 Homeland system

- 4 Forced removals

- 5 Petty apartheid

- 6 Coloured classification

- 7 Women under apartheid

- 8 Sport under apartheid

- 9 Asians during apartheid

- 10 Conservatism

- 11 Internal resistance

- 12 International relations

- 13 State security

- 14 Final years of apartheid

- 15 Contrition

- 16 See also

- 17 References

- 18 Further reading

- 19 External links

Precursors of apartheid[edit]

Under the 1806 Cape Articles of Capitulation[11] the new British colonial rulers were required to respect previous legislation enacted under Roman Dutch law[12] and this led to a separation of the law in South Africa from English Common Law and a high degree of legislative autonomy. The governors and assemblies that governed the legal process in the various colonies of South Africa were launched on a different and independent legislative path from the rest of the British Empire.

In the days of slavery, slaves required passes to travel away from their masters. In 1797 the Landdrost and Heemraden of Swellendam and Graaff-Reinett (the Dutch colonial governing authority) extended pass laws beyond slaves and ordained that all Khoikhoi (Hottentots) moving about the country for any purpose should carry passes.[6] This was confirmed by the British Colonial government in 1809 by the Hottentot Proclamation, which decreed that if a Khoikhoi were to move they would need a pass from their master or a local official.[6] Ordinance No. 49 of 1828 decreed that prospective black immigrants were to be granted passes for the sole purpose of seeking work.[6] These passes were to be issued for Coloureds and Khoikhoi, but not for other Africans, but other Africans were still forced to carry passes.

The United Kingdom's Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73) abolished slavery throughout the British Empire and overrode the Cape Articles of Capitulation. To comply with the act the South African legislation was expanded to include Ordinance 1 in 1835, which effectively changed the status of slaves to indentured labourers. This was followed by Ordinance 3 in 1848, which introduced an indenture system for Xhosa that was little different from slavery. The various South African colonies passed legislation throughout the rest of the nineteenth century to limit the freedom of unskilled workers, to increase the restrictions on indentured workers and to regulate the relations between the races.

The Franchise and Ballot Act of 1892 instituted limits based on financial means and education to the black franchise,[13] and the Natal Legislative Assembly Bill of 1894 deprived Indians of the right to vote.[14] In 1905 the General Pass Regulations Act denied blacks the vote, limited them to fixed areas and inaugurated the infamous Pass System.[15] The Asiatic Registration Act (1906) required all Indians to register and carry passes.[16] In 1910 the Union of South Africa was created as a self-governing dominion, which continued the legislative programme: the South Africa Act (1910) enfranchised whites, giving them complete political control over all other racial groups while removing the right of blacks to sit in parliament,[17] the Native Land Act (1913) prevented blacks, except those in the Cape, from buying land outside "reserves",[17] the Natives in Urban Areas Bill (1918) was designed to force blacks into "locations",[18] the Urban Areas Act (1923) introducedresidential segregation and provided cheap labour for industry led by white people, the Colour Bar Act (1926) prevented blacks from practising skilled trades, the Native Administration Act (1927) made the British Crown, rather than paramount chiefs, the supreme head over all African affairs,[19] the Native Land and Trust Act (1936) complemented the 1913 Native Land Act and, in the same year, the Representation of Natives Act removed previous black voters from the Cape voters' roll and allowed them to elect three whites to Parliament.[20] One of the first pieces of segregating legislation enacted by Jan Smuts' United Party government was the Asiatic Land Tenure Bill (1946), which banned land sales to Indians.[21]

The United Party government began to move away from the rigid enforcement of segregationist laws during World War II.[22] Amid fears integration would eventually lead to racial assimilation, the legislature established the Sauer Commission to investigate the effects of the United Party's policies. The commission concluded that integration would bring about a "loss of personality" for allracial groups.

Institution of apartheid[edit]

The election of 1948[edit]

Main article: South African general election, 1948

In the run-up to the 1948 elections, the main Afrikaner nationalist party, the Herenigde Nasionale Party (Reunited National Party) under the leadership of Protestant cleric Daniel Francois Malancampaigned on its policy of apartheid.[23][24] The NP narrowly defeated Smuts's United Party and formed a coalition government with another Afrikaner nationalist party, the Afrikaner Party. Malan became the first apartheid prime minister, and the two parties later merged to form the National Party (NP).

Apartheid legislation[edit]

| Apartheid legislation in South Africa |

|---|

| † No new legislation introduced, rather the existing legislation named was amended. |

Main article: Apartheid legislation in South Africa

NP leaders argued that South Africa did not comprise a single nation, but was made up of four distinct racial groups: white, black, coloured and Indian. These groups were split into 13 nations or racial federations. White people encompassed the English and Afrikaans language groups; the black populace was divided into ten such groups.

The state passed laws that paved the way for "grand apartheid", which was centred on separating races on a large scale, by compelling people to live in separate places defined by race. This strategy was in part adopted from "left-over" British rule that separated different racial groups after they took control of the Boer republics in the Anglo-Boer war. This created the black-only "townships" or "locations", where blacks were relocated to their own towns. In addition, "petty apartheid" laws were passed. The principal apartheid laws were as follows.[25]

The first grand apartheid law was the Population Registration Act of 1950, which formalised racial classification and introduced an identity card for all persons over the age of 18, specifying their racial group.[26] Official teams or Boards were established to come to a conclusion on those people whose race was unclear.[27] This caused difficulty, especially for coloured people, separating their families when members were allocated different races.[28]

The second pillar of grand apartheid was the Group Areas Act of 1950.[29] Until then, most settlements had people of different races living side by side. This Act put an end to diverse areas and determined where one lived according to race. Each race was allotted its own area, which was used in later years as a basis of forced removal.[30] The Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act of 1951 allowed the government to demolish black shanty town slums and forced white employers to pay for the construction of housing for those black workers who were permitted to reside in cities otherwise reserved for whites.[31]

The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 prohibited marriage between persons of different races, and the Immorality Act of 1950 made sexual relations with a person of a different race acriminal offence.

Under the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act of 1953, municipal grounds could be reserved for a particular race, creating, among other things, separate beaches, buses, hospitals, schools and universities. Signboards such as "whites only" applied to public areas, even including park benches.[32] Blacks were provided with services greatly inferior to those of whites, and, to a lesser extent, to those of Indian and coloured people.[8]

Further laws had the aim of suppressing resistance, especially armed resistance, to apartheid. The Suppression of Communism Act of 1950 banned any party subscribing to Communism. The act defined Communism and its aims so sweepingly that anyone who opposed government policy risked being labelled as a Communist. Since the law specifically stated that Communism aimed to disrupt racial harmony, it was frequently used to gag opposition to apartheid. Disorderly gatherings were banned, as were certain organisations that were deemed threatening to the government.

Education was segregated by the 1953 Bantu Education Act, which crafted a separate system of education for African students and was designed to prepare black people for lives as a labouring class.[33] In 1959 separate universities were created for black, coloured and Indian people. Existing universities were not permitted to enroll new black students. The Afrikaans Medium Decree of 1974 required the use of Afrikaans and English on an equal basis in high schools outside the homelands.[34]

The Bantu Authorities Act of 1951 created separate government structures for blacks and whites and was the first piece of legislation to support the government's plan of separate development in the Bantustans. The Promotion of Black Self-Government Act of 1959 entrenched the NP policy of nominally independent "homelands" for blacks. So-called "self–governing Bantu units" were proposed, which would have devolved administrative powers, with the promise later of autonomy and self-government. It also abolished the seats of white representatives of Africans and removed from the rolls the few blacks still qualified to vote. The Bantu Investment Corporation Act of 1959 set up a mechanism to transfer capital to the homelands in order to create employment there. Legislation of 1967 allowed the government to stop industrial development in "white" cities and redirect such development to the "homelands". The Black Homeland Citizenship Act of 1970 marked a new phase in the Bantustan strategy. It changed the status of blacks to citizens of one of the ten autonomous territories. The aim was to ensure a demographic majority of white people within South Africa by having all ten Bantustans achieve full independence.

Interracial contact in sport was frowned upon, but there were no segregatory sports laws.

The government tightened pass laws compelling blacks to carry identity documents, to prevent the immigration of blacks from other countries. To reside in a city, blacks had to be in employment there. Until 1956 women were for the most part excluded from these pass requirements, as attempts to introduce pass laws for women were met with fierce resistance.[35]

Disenfranchisement of coloured voters[edit]

Main article: Coloured vote constitutional crisis

In 1950, D F Malan announced the NP's intention to create a Coloured Affairs Department.[36] J.G. Strijdom, Malan's successor as Prime Minister, moved to strip voting rights from black and coloured residents of the Cape Province. The previous government had introduced the Separate Representation of Voters Bill into Parliament in 1951; however, four voters, G Harris, W D Franklin, W D Collins and Edgar Deane, challenged its validity in court with support from the United Party.[37] The Cape Supreme Court upheld the act, but reversed by the Appeal Court, finding the act invalid because a two-thirds majority in a joint sitting of both Houses of Parliament was needed in order to change the entrenched clauses of the Constitution.[38] The government then introduced the High Court of Parliament Bill (1952), which gave Parliament the power to overrule decisions of the court.[39] The Cape Supreme Court and the Appeal Court declared this invalid too.[40]

In 1955 the Strijdom government increased the number of judges in the Appeal Court from five to 11, and appointed pro-Nationalist judges to fill the new places.[41] In the same year they introduced the Senate Act, which increased the Senate from 49 seats to 89.[42] Adjustments were made such that the NP controlled 77 of these seats.[43] The parliament met in a joint sitting and passed the Separate Representation of Voters Act in 1956, which transferred coloured voters from the common voters' roll in the Cape to a new coloured voters' roll.[44] Immediately after the vote, the Senate was restored to its original size. The Senate Act was contested in the Supreme Court, but the recently enlarged Appeal Court, packed with government-supporting judges, upheld the act, and also the Act to remove coloured voters.[45]

The 1956 law allowed Coloureds to elect four whites to Parliament, but a 1969 law abolished those seats and stripped Coloureds of their right to vote. Since Asians had never been allowed to vote, this resulted in whites being the sole enfranchised group.

Unity among white South Africans[edit]

Before South Africa became a republic, politics among white South Africans was typified by the division between the mainly Afrikaner pro-republic conservative and the largely English anti-republican liberal sentiments,[46] with the legacy of the Boer War still a factor for some people. Once the status of a republic was attained, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd called for improved relations and greater accord between those of British descent and the Afrikaners.[47] He claimed that the only difference now was between those who supported apartheid and those in opposition to it. The ethnic divide would no longer be between Afrikaans speakers and English speakers, but rather white and black ethnicities. Most Afrikaners supported the notion of unanimity of white people to ensure their safety. White voters of British descent were divided. Many had opposed a republic, leading to a majority "no" vote in Natal.[48] Later, some of them recognised the perceived need for white unity, convinced by the growing trend of decolonisation elsewhere in Africa, which concerned them. British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan's "Wind of Change" speech left the British faction feeling that Britain had abandoned them.[49] The more conservative English-speakers gave support to Verwoerd;[50] others were troubled by the severing of ties with Britain and remained loyal to the Crown.[51] They were acutely displeased at the choice between British and South African nationality. Although Verwoerd tried to bond these different blocs, the subsequent ballot illustrated only a minor swell of support,[52] indicating that a great many English speakers remained apathetic, and that Verwoerd had not succeeded in uniting the white population, and a divide between Anglo and Afrikaner whites remained.

Homeland system[edit]

Main article: Bantustan

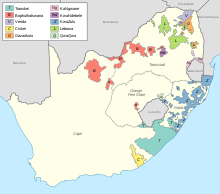

Under the homeland system, the government attempted to divide South Africa into a number of separate states, each of which was supposed to develop into a separate nation-state for a different ethnic group.[53]

Territorial separation was not a new institution. There were, for example, the "reserves" created under the British government in the nineteenth century. Under apartheid, 13 per cent of the land was reserved for black homelands, a relatively small amount compared to the total population, and generally in economically unproductive areas of the country. The Tomlinson Commission of 1954 justified apartheid and the homeland system, but stated that additional land ought to be given to the homelands, a recommendation that was not carried out.[citation needed]

When Verwoerd became Prime Minister in 1958, the policy of "separate development" came into being, with the homeland structure as one of its cornerstones. Verwoerd came to believe in the granting of independence to these homelands. The government justified its plans on the basis that "(the) government's policy is, therefore, not a policy of discrimination on the grounds of race or colour, but a policy of differentiation on the ground of nationhood, of different nations, granting to each self-determination within the borders of their homelands – hence this policy of separate development".[citation needed] Under the homelands system, blacks would no longer be citizens of South Africa, becoming citizens of the independent homelands who worked in South Africa as foreign migrant labourers on temporary work permits. In 1958 the Promotion of Black Self-Government Act was passed, and border industries and the Bantu Investment Corporation were established to promote economic development and the provision of employment in or near the homelands. Many black South Africans who had never resided in their identified homeland were forcibly removed from the cities to the homelands.

Ten homelands were allocated to different black ethnic groups: Lebowa (North Sotho, also referred to as Pedi), QwaQwa (South Sotho),Bophuthatswana (Tswana), KwaZulu (Zulu), KaNgwane (Swazi), Transkei and Ciskei (Xhosa), Gazankulu (Tsonga), Venda (Venda) and KwaNdebele(Ndebele). Four of these were declared independent by the South African government: Transkei in 1976, Bophuthatswana in 1977, Venda in 1979, and Ciskei in 1981 (known as the TBVC states). Once a homeland was granted its nominal independence, its designated citizens had their South African citizenship revoked, replaced with citizenship in their homeland. These people were then issued passports instead of passbooks. Citizens of the nominally autonomous homelands also had their South African citizenship circumscribed, meaning they were no longer legally considered South African.[54] The South African government attempted to draw an equivalence between their view of black citizens of the homelands and the problems which other countries faced through entry of illegal immigrants.

International recognition of the Bantustans[edit]

International recognition for these new countries was extremely limited. Each TBVC state extended recognition to the other independent Bantustans while South Africa showed its commitment to the notion of TBVC sovereignty by building embassies in the various TBVC capitals. Israel was the only internationally recognised country and UN member to afford some sort of diplomatic recognition to any of the Bantustans, though formal acknowledgment of the Bantustans as full-fledged countries never occurred.[55] In late 1982, the Ciskei Trade Mission opened in Tel Aviv, flying its own flag and staffed by two Israelis, Yosef Schneider and Nat Rosenwasser, who were employed by the Ciskei Foreign Ministry. Bophuthatswana also had a representative in Israel, Shabtai Kalmanovich,[55] who in 1988 was sentenced by Israel to seven years in jail for spying for the KGB.[56] In 1983 Israel was visited by the presidents of Bophuthatswana and Ciskei, and by Venda’s entire chamber of commerce.[55] During this visit Lennox Sebe, the Ciskeian President, secured a contract with the Israeli government to supply and train his armed forces.[55] Initially, six planes – at least one a military helicopter – were sold to Ciskei, and 18 Ciskei residents arrived in Israel for pilot training.[55] In 1985 Israel received Buthelezi as Chief Minister of KwaZulu during an unofficial visit.[55]

Forced removals [edit]

During the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, the government implemented a policy of 'resettlement', to force people to move to their designated "group areas". Millions of people were forced to relocate. These removals included people relocated due to slum clearance programmes, labour tenants on white-owned farms, the inhabitants of the so-called 'black spots' (black-owned land surrounded by white farms), the families of workers living in townships close to the homelands, and 'surplus people' from urban areas, including thousands of people from the Western Cape (which was declared a 'Coloured Labour Preference Area'[57]) who were moved to the Transkei and Ciskei homelands. The best-publicised forced removals of the 1950s occurred in Johannesburg, when 60,000 people were moved to the new township of Soweto (an abbreviation for South Western Townships).[58][59]

Until 1955 Sophiatown had been one of the few urban areas where blacks were allowed to own land, and was slowly developing into a multiracial slum. As industry in Johannesburg grew, Sophiatown became the home of a rapidly expanding black workforce, as it was convenient and close to town. It had the only swimming pool for black children in Johannesburg.[60] As one of the oldest black settlements in Johannesburg, it held an almost symbolic importance for the 50,000 blacks it contained, both in terms of its sheer vibrancy and its unique culture. Despite a vigorous ANC protest campaign and worldwide publicity, the removal of Sophiatown began on 9 February 1955 under the Western Areas Removal Scheme. In the early hours, heavily armed police forced residents out of their homes and loaded their belongings onto government trucks. The residents were taken to a large tract of land, 13 miles (19 km) from the city centre, known as Meadowlands, which the government had purchased in 1953. Meadowlands became part of a new planned black city called Soweto. Sophiatown was destroyed by bulldozers, and a new white suburb named Triomf (Triumph) was built in its place. This pattern of forced removal and destruction was to repeat itself over the next few years, and was not limited to people of African descent. Forced removals from areas like Cato Manor (Mkhumbane) in Durban, and District Six in Cape Town, where 55,000 coloured and Indian people were forced to move to new townships on the Cape Flats, were carried out under the Group Areas Act of 1950. Nearly 600,000 coloured, Indian and Chinese people were moved under the Group Areas Act. Some 40,000 whites were also forced to move when land was transferred from "white South Africa" into the black homelands.[citation needed]

Petty apartheid[edit]

The NP passed a string of legislation that became known as petty apartheid. The first of these was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act 55 of 1949, prohibiting marriage between whites and people of other races. The Immorality Amendment Act 21 of 1950 (as amended in 1957 by Act 23) forbade "unlawful racial intercourse" and "any immoral or indecent act" between a white and an African, Indian or coloured person.

Blacks were not allowed to run businesses or professional practices in areas designated as "white South Africa" unless they had a permit. They were required to move to the black "homelands" and set up businesses and practices there. Transport and civil facilities were segregated. Black buses stopped at black bus stops and white buses at white ones. Trains, hospitals and ambulances were segregated.[61] Because of the smaller numbers of white patients and the fact that white doctors preferred to work in white hospitals, conditions in white hospitals were much better than those in often overcrowded and understaffed black hospitals.[62] Blacks were excluded from living or working in white areas, unless they had a pass, nicknamed the dompas ("dumb pass" in Afrikaans). Only blacks with "Section 10" rights (those who had migrated to the cities before World War II) were excluded from this provision. A pass was issued only to a black with approved work. Spouses and children had to be left behind in black homelands. A pass was issued for one magisterial district (usually one town) confining the holder to that area only. Being without a valid pass made a person subject to arrest and trial for being an illegal migrant. This was often followed by deportation to the person's homeland and prosecution of the employer for employing an illegal migrant. Police vans patrolled white areas to round up blacks without passes. Blacks were not allowed to employ whites in white South Africa.[citation needed]

Although trade unions for black and coloured (mixed race) workers had existed since the early 20th century, it was not until the 1980s reforms that a mass black trade union movement developed. Trade unions under apartheid were racially segregated, with 54 unions being white only, 38 for Indian and coloured and 19 for African people. The Industrial Conciliation Act (1956) legislated against the creation of multi-racial trade unions and attempted to split existing multi-racial unions into separate branches or organisations along racial lines.[63]

In the 1970s the state spent ten times more per child on the education of white children than on black children within the Bantu Education system (the education system in black schools within white South Africa). Higher education was provided in separate universities and colleges after 1959. Eight black universities were created in the homelands. Fort Hare University in the Ciskei (now Eastern Cape) was to register only Xhosa-speaking students. Sotho,Tswana, Pedi and Venda speakers were placed at the newly founded University College of the North at Turfloop, while the University College of Zululandwas launched to serve Zulu scholars. Coloureds and Indians were to have their own establishments in the Cape and Natal respectively.[citation needed]

Each black homeland controlled its own education, health and police systems. Blacks were not allowed to buy hard liquor. They were able only to buy state-produced poor quality beer (although this was relaxed later). Public beaches were racially segregated. Public swimming pools, some pedestrian bridges, drive-in cinema parking spaces, graveyards, parks, and public toilets were segregated. Cinemas and theatres in white areas were not allowed to admit blacks. There were practically no cinemas in black areas. Most restaurants and hotels in white areas were not allowed to admit blacks except as staff. Blacks were prohibited from attending white churches under the Churches Native Laws Amendment Act of 1957, but this was never rigidly enforced and churches were one of the few places races could mix without the interference of the law. Blacks earning 360 rand a year or more had to pay taxes while the white threshold was more than twice as high, at 750 rand a year. On the other hand, the taxation rate for whites was considerably higher than that for blacks.[citation needed]

Blacks could never acquire land in white areas. In the homelands, much of the land belonged to a 'tribe', where the local chieftain would decide how the land had to be used. This resulted in whites owning almost all the industrial and agricultural lands and much of the prized residential land. Most blacks were stripped of their South African citizenship when the "homelands" became "independent", and they were no longer able to apply for South African passports. Eligibility requirements for a passport had been difficult for blacks to meet, the government contending that a passport was a privilege, not a right, and the government did not grant many passports to blacks. Apartheid pervaded culture as well as the law, and was entrenched by most of the mainstream media.

Coloured classification[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

| Specific forms |

Main article: Coloured

The population was classified into four groups: Black, White, Indian, and Coloured (capitalised to denote their legal definitions in South African law). The Coloured group included people regarded as being of mixed descent, including of Bantu, Khoisan, European and Malay ancestry. Many were descended from people brought to South Africa from other parts of the world, such as India, Madagascar, China and the Philippines, as slaves and indentured workers.[64]

The apartheid bureaucracy devised complex (and often arbitrary) criteria at the time that the Population Registration Act was implemented to determine who was Coloured. Minor officials would administer tests to determine if someone should be categorised either Coloured or Black, or if another person should be categorised either Coloured or White. Different members of the same family found themselves in different race groups. Further tests determined membership of the various sub-racial groups of the Coloureds. Many of those who formerly belonged to this racial group are opposed to the continuing use of the term "coloured" in the post-apartheid era, though the term no longer signifies any legal meaning. The expressions 'so-called Coloured' (Afrikaans sogenaamde Kleurlinge) and 'brown people' (bruinmense) acquired a wide usage in the 1980s.

Discriminated against by apartheid, Coloureds were as a matter of state policy forced to live in separate townships, in some cases leaving homes their families had occupied for generations, and received an inferior education, though better than that provided to Blacks.[citation needed] They played an important role in the anti-apartheid movement: for example the African Political Organization established in 1902 had an exclusively Coloured membership.

Voting rights were denied to Coloureds in the same way that they were denied to Blacks from 1950 to 1983. However, in 1977 the NP caucus approved proposals to bring Coloureds and Indians into central government. In 1982, final constitutional proposals produced a referendum among Whites, and theTricameral Parliament was approved. The Constitution was reformed the following year to allow the Coloured and Asian minorities participation in separate Houses in a Tricameral Parliament, and Botha became the first Executive State President. The idea was that the Coloured minority could be granted voting rights, but the Black majority were to become citizens of independent homelands. These separate arrangements continued until the abolition of apartheid. The Tricameral reforms led to the formation of the (anti-apartheid) UDF as a vehicle to try to prevent the co-option of Coloureds and Indians into an alliance with Whites. The battles between the UDF and the NP government from 1983 to 1989 were to become the most intense period of struggle between left-wing and right-wing South Africans.

TO BE CONTINUED

MANY HAVE TRIED TO USE THE BIBLE TO UPHOLD SEGREGATION AND DISCRIMINATION. THEY HAVE PERVERTED AND TWISTED THE BIBLE FOR THEIR OWN ENDS.

THEY READ THE BIBLE WITH TUNNEL VISION, DELIBERATELY OVERLOOKING SOME PLAIN WORDS FROM THE ALMIGHTY GOD WHO CREATED ALL RACES AND PEOPLES.

"ONE LAW SHALL BE TO HIM THAT IS HOMEBORN, AND UNTO THE STRANGER THAT SOJOURNETH AMONG YOU" (EXODUS 12:49).

IF THAT WAS NOT GOOD ENOUGH TO SAY ONCE, GOD REPEATED IT TWICE MORE:

"....YOU SHALL HAVE ONE ORDINANCE, BOTH FOR THE STRANGER, AND FOR HIM THAT WAS BORN IN THE LAND" (NUMBERS 9:14).

"ONE ORDINANCE SHALL BE BOTH FOR YOU OF THE CONGREGATION, AND ALSO FOR THE STRANGER THAT SOJOURETH WITH YOU, AN ORDINANCE FOR EVER IN YOUR GENERATIONS: AS YOU ARE, SO SHALL THE STRANGR BE BEFORE THE LORD. ONE LAW AND ONE MANNER SHALL BE FOR YOU, AND FOR THE STRANGER THAT SOJOURETH WITH YOU" (NUMBERS 15:15,16).

IF ISRAEL HAD OBEYED GOD THIS WOULD BE THE END RESULT:

"NOW THEREFORE HEARKEN O ISRAEL UNTO THE STATUTES AND JUDGMENTS, WHICH I TEACH YOU......YOU SHALL NOT ADD UNTO THE WORDS WHICH I COMMAND YOU, NEITHER SHALL YOU DIMINISH AUGHT FROM IT, THAT YOU MAY KEEP THE COMMANDMENTS OF THE LORD YOUR GOD......BEHOLD, I HAVE TAUGHT YOU STATUTES AND JUDGMENTS, EVEN AS THE LORD MY GOD COMMANDED ME, THAT YOU SHOULD DO SO IN THE LAND WHITHER YOU GO TO POSSES IT. KEEP THEREFORE AND DO THEM, FOR THIS IS YOUR WISDOM AND YOUR UNDERSTANDING IN THE SIGHT OF THE NATIONS, WHICH SHALL HEAR OF THESE STSTUTES, AND SAY, SURELY THIS GREAT NATION IS A WISE AND UNDERSTANDING PEOPLE. FOR WHAT NATION IS THERE SO GREAT, WHO HAS GOD SO NIGH UNTO THEM,....AND WHAT NATION IS THERE SO GREAT, THAT HAS STATUTES AND JUDGMENTS SO RIGHTEOUS AS ALL THIS LAW, WHICH I SET BEFORE YOU THIS DAY"

(DEUTERONOMY 4:1-8).

THE ANGLO-SAXON-CELTIC NATIONS ARE OF THE TEN TRIBES OF THE HOUSE OF ISRAEL. NOT TOO FAR BACK WE FOUNDED OUR NATIONS ON THE BIBLE.....WE PRIDED OURSELVES AS BEING "CHRISTIAN" NATIONS.....WE PRIDED OURSELVES AS A MISSIONARY PEOPLE, AS A PEOPLE GIVING THE BIBLE TO THE WORLD. BUT WE READ AND FOLLOWED IT WITH TUNNEL VISION, JUST PICKING VERSES THAT WE WANTED TO FIT OUR EXPANSION AS WE EXPANDED AROUND THE WORLD, ESPECIALLY IN THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH AND AMERICAN EXPANSIONS.

WE HAVE SINNED IN MANY WAYS, GREAT SINS, OVER THE LAST NUMBER OF HUNDREDS OF YEARS. WE FINALLY LEARNT SOME OF THOSE SINS AND WE REPENTED AND CHANGED OUR WAYS, REALIZING WE WERE NOT DOING THE RIGHT AND CORRECT WAYS OF THE LORD, AS WE MOVED AND BUILT UP LANDS; WE MADE CHANGES TOWARDS THE STRANGERS SO TO SPEAK IN THE LANDS GOD GAVE US, TO FULFIL THE PHYSICAL PROMISES HE MADE TO ABRAHAM, ISAAC, JACOB, AND JOSEPH.

TODAY OUR LANDS SIN IN MANY OTHER DIFFERENT WAYS, CASTING OUT THE BIBLE FROM OUR GOVERNMENTS AND INSTITUTIONS BEING THE MAIN PROBLEM, HENCE LEADING TO NATIONAL SINS. IT WOULD SEEM WE HAVE GONE OVER THE LINE OF NO RETURN, AND SO THE END TIME PROPHECIES OF OUR DESTRUCTION FROM OUR LOVERS MUST COME TO PASS, AS FORETOLD IN THE BOOK OF EZEKIEL AND OTHER PROPHECIES OF THE BIBLE.

HERE IN THIS SERIES OF STUDIES ON APARTHEID WE CAN SEE THE ERRORS, MISTAKES AND SINS OF THE PAST, BUT SAD TO SAY OUR PRESENT SINS WE DO NOT SEE.....WE SHALL, BUT NOT BEFORE WE ARE BROUGHT TO OUR KNEES BEFORE THE RETURN OF CHRIST. HE WILL COME AND HE WILL DELIVER US FROM OUR DESOLATION AND OUR SINS. THEN FINALLY IN THE AGE TO COME, WE SHALL FULFIL DEUTERONOMY 4, AND BE A BLAZING RIGHTEOUS LIGHT TO ALL NATIONS OF THE WORLD.

MANY HAVE TRIED TO USE THE BIBLE TO UPHOLD SEGREGATION AND DISCRIMINATION. THEY HAVE PERVERTED AND TWISTED THE BIBLE FOR THEIR OWN ENDS.

THEY READ THE BIBLE WITH TUNNEL VISION, DELIBERATELY OVERLOOKING SOME PLAIN WORDS FROM THE ALMIGHTY GOD WHO CREATED ALL RACES AND PEOPLES.

"ONE LAW SHALL BE TO HIM THAT IS HOMEBORN, AND UNTO THE STRANGER THAT SOJOURNETH AMONG YOU" (EXODUS 12:49).

IF THAT WAS NOT GOOD ENOUGH TO SAY ONCE, GOD REPEATED IT TWICE MORE:

"....YOU SHALL HAVE ONE ORDINANCE, BOTH FOR THE STRANGER, AND FOR HIM THAT WAS BORN IN THE LAND" (NUMBERS 9:14).

"ONE ORDINANCE SHALL BE BOTH FOR YOU OF THE CONGREGATION, AND ALSO FOR THE STRANGER THAT SOJOURETH WITH YOU, AN ORDINANCE FOR EVER IN YOUR GENERATIONS: AS YOU ARE, SO SHALL THE STRANGR BE BEFORE THE LORD. ONE LAW AND ONE MANNER SHALL BE FOR YOU, AND FOR THE STRANGER THAT SOJOURETH WITH YOU" (NUMBERS 15:15,16).

IF ISRAEL HAD OBEYED GOD THIS WOULD BE THE END RESULT:

"NOW THEREFORE HEARKEN O ISRAEL UNTO THE STATUTES AND JUDGMENTS, WHICH I TEACH YOU......YOU SHALL NOT ADD UNTO THE WORDS WHICH I COMMAND YOU, NEITHER SHALL YOU DIMINISH AUGHT FROM IT, THAT YOU MAY KEEP THE COMMANDMENTS OF THE LORD YOUR GOD......BEHOLD, I HAVE TAUGHT YOU STATUTES AND JUDGMENTS, EVEN AS THE LORD MY GOD COMMANDED ME, THAT YOU SHOULD DO SO IN THE LAND WHITHER YOU GO TO POSSES IT. KEEP THEREFORE AND DO THEM, FOR THIS IS YOUR WISDOM AND YOUR UNDERSTANDING IN THE SIGHT OF THE NATIONS, WHICH SHALL HEAR OF THESE STSTUTES, AND SAY, SURELY THIS GREAT NATION IS A WISE AND UNDERSTANDING PEOPLE. FOR WHAT NATION IS THERE SO GREAT, WHO HAS GOD SO NIGH UNTO THEM,....AND WHAT NATION IS THERE SO GREAT, THAT HAS STATUTES AND JUDGMENTS SO RIGHTEOUS AS ALL THIS LAW, WHICH I SET BEFORE YOU THIS DAY"

(DEUTERONOMY 4:1-8).

THE ANGLO-SAXON-CELTIC NATIONS ARE OF THE TEN TRIBES OF THE HOUSE OF ISRAEL. NOT TOO FAR BACK WE FOUNDED OUR NATIONS ON THE BIBLE.....WE PRIDED OURSELVES AS BEING "CHRISTIAN" NATIONS.....WE PRIDED OURSELVES AS A MISSIONARY PEOPLE, AS A PEOPLE GIVING THE BIBLE TO THE WORLD. BUT WE READ AND FOLLOWED IT WITH TUNNEL VISION, JUST PICKING VERSES THAT WE WANTED TO FIT OUR EXPANSION AS WE EXPANDED AROUND THE WORLD, ESPECIALLY IN THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH AND AMERICAN EXPANSIONS.

WE HAVE SINNED IN MANY WAYS, GREAT SINS, OVER THE LAST NUMBER OF HUNDREDS OF YEARS. WE FINALLY LEARNT SOME OF THOSE SINS AND WE REPENTED AND CHANGED OUR WAYS, REALIZING WE WERE NOT DOING THE RIGHT AND CORRECT WAYS OF THE LORD, AS WE MOVED AND BUILT UP LANDS; WE MADE CHANGES TOWARDS THE STRANGERS SO TO SPEAK IN THE LANDS GOD GAVE US, TO FULFIL THE PHYSICAL PROMISES HE MADE TO ABRAHAM, ISAAC, JACOB, AND JOSEPH.

TODAY OUR LANDS SIN IN MANY OTHER DIFFERENT WAYS, CASTING OUT THE BIBLE FROM OUR GOVERNMENTS AND INSTITUTIONS BEING THE MAIN PROBLEM, HENCE LEADING TO NATIONAL SINS. IT WOULD SEEM WE HAVE GONE OVER THE LINE OF NO RETURN, AND SO THE END TIME PROPHECIES OF OUR DESTRUCTION FROM OUR LOVERS MUST COME TO PASS, AS FORETOLD IN THE BOOK OF EZEKIEL AND OTHER PROPHECIES OF THE BIBLE.

HERE IN THIS SERIES OF STUDIES ON APARTHEID WE CAN SEE THE ERRORS, MISTAKES AND SINS OF THE PAST, BUT SAD TO SAY OUR PRESENT SINS WE DO NOT SEE.....WE SHALL, BUT NOT BEFORE WE ARE BROUGHT TO OUR KNEES BEFORE THE RETURN OF CHRIST. HE WILL COME AND HE WILL DELIVER US FROM OUR DESOLATION AND OUR SINS. THEN FINALLY IN THE AGE TO COME, WE SHALL FULFIL DEUTERONOMY 4, AND BE A BLAZING RIGHTEOUS LIGHT TO ALL NATIONS OF THE WORLD.

No comments:

Post a Comment